The Evolution of Dokémon (2.0)

In an earlier post, i explained the start of Dokémon, and how my brother, David, and I used printer paper, cardboard from toilet paper rolls, and an arsenal of pens and markers to create cards depicting family members and friends in more bestial forms. For example, in the Dokémon world, the Russell Squirmy represented me, and the Wild David represented my brother.

In an earlier post, i explained the start of Dokémon, and how my brother, David, and I used printer paper, cardboard from toilet paper rolls, and an arsenal of pens and markers to create cards depicting family members and friends in more bestial forms. For example, in the Dokémon world, the Russell Squirmy represented me, and the Wild David represented my brother.

As time went on, we got our hands on actual Pokémon cards. Real, tangilble, impossibly beautiful Pokémon cards! This only occured after an early blunder, in which we bought Pokémon info cards at a 7-11, instead of the Pokémon playing cards we desired. But we finally got a starter set each, spearheaded by a holographic Machamp.

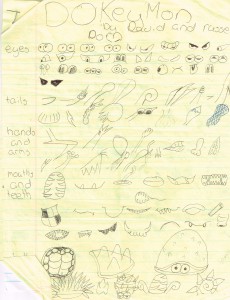

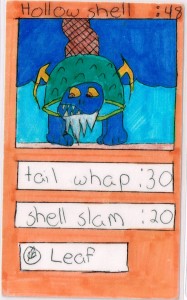

Before getting our hands on the playing cards, we had the Pokémon television show, which aired every Saturday. Using the show proved to be an effective, but much more strenuous way of collecting information about each of the characters, for at the end of each episode a segment played, which flashed each of the 150 original Pokémon. David and I had our pens and lined paper ready for this segment. When it aired, we plucked various types of Pokémon eyes out, hacked off limbs, wings and tails (figuratively, of course), and jotted as many as we could down. The two images of line paper, shown above, illustrate a small portion of the notes we took fro m these sessions of butchery. From these sheets we selected pieces and Frankenstien’d them together to create new Dokémon. The image of Hollowshell to the left is an example of one of the many early Dokémon that came from the combination of pieces taken from the notes we made. You can see the turtle-like shell, the jagged teeth, the beaver tail, and the claws, each of which came from a different Pokémon.

m these sessions of butchery. From these sheets we selected pieces and Frankenstien’d them together to create new Dokémon. The image of Hollowshell to the left is an example of one of the many early Dokémon that came from the combination of pieces taken from the notes we made. You can see the turtle-like shell, the jagged teeth, the beaver tail, and the claws, each of which came from a different Pokémon.

These earlier Dokémon continue the genetic line of the original toilet paper Dokémon. However, by the time we upgraded from hand crafted 2X3 cards to 3X4 index cards, we had exhausted our list of relatives and friends in which to name them after.

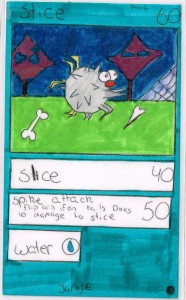

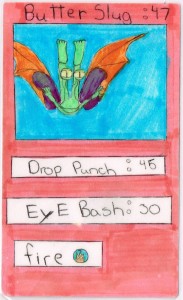

Thus we came up with literal compound names such as Hollowshell and Butterslug, as he looks to be a mix between a butterfly and a slug, and variations of descriptive words that portray the particular Dokémon, such as Stice, from the English word Slice, as the Dokémon is very sharp and able to slice victims, which its basic 40 damage attack attests to.

Thus we came up with literal compound names such as Hollowshell and Butterslug, as he looks to be a mix between a butterfly and a slug, and variations of descriptive words that portray the particular Dokémon, such as Stice, from the English word Slice, as the Dokémon is very sharp and able to slice victims, which its basic 40 damage attack attests to.

After this period of using parts of Pokémon, as well as the animals of our world, to make unqiue Dokémon, David and I entered a period that i like to describe as the dark ages of Dokémon. We took a step back with the knock-off card game, as it became exactly that: a knock-off–a clone of the popular Pokémon franchise. This period in time came with the introduction of real Pokémon cards. As i mentioned, after the 7-11 mistake, we received real Pokémon playing cards, and began to make copies of them. We often changed the creatures’ abilities, and letter of their names, but the look of the creatures changed little when being translated from the polished Pokémon cards to the matte index cards of Dokémon.

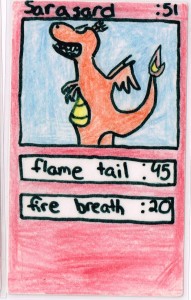

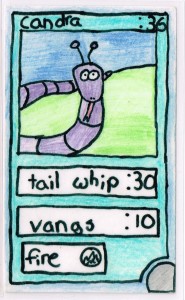

As you can see, Sarasard is a copy of Charizard, even having a very similar name, and Candra is a clone of Ekans, except with antennae and cartoonish eyes. In these early Dokémon we also used not only odd numbers, but obsure ones, such as Sarasard’s 51 HP (Health Points), and 45 Flame tail, as well as Candra’s 36 HP. During this time, David and I, also fine tuned the look of the cards. Comparing just these two cards you can see the plainer Sarasard solid red border, in comparison to Candra’s two toned blue one, with the gray thumb slot. Both cards illustrate the simplicity of early Dokémon with the very basic names for their skill sets. Flame tail and Fire breath for Sarasard, and Tail whip and Vangs for Candra. In addition, Candra’s card includes a box for its weakness to fire, which is ironic, in a way, for though Sarasard is a fire Dokémon it remains a weaker card in terms of aesthetic design.

As you can see, Sarasard is a copy of Charizard, even having a very similar name, and Candra is a clone of Ekans, except with antennae and cartoonish eyes. In these early Dokémon we also used not only odd numbers, but obsure ones, such as Sarasard’s 51 HP (Health Points), and 45 Flame tail, as well as Candra’s 36 HP. During this time, David and I, also fine tuned the look of the cards. Comparing just these two cards you can see the plainer Sarasard solid red border, in comparison to Candra’s two toned blue one, with the gray thumb slot. Both cards illustrate the simplicity of early Dokémon with the very basic names for their skill sets. Flame tail and Fire breath for Sarasard, and Tail whip and Vangs for Candra. In addition, Candra’s card includes a box for its weakness to fire, which is ironic, in a way, for though Sarasard is a fire Dokémon it remains a weaker card in terms of aesthetic design.

As time went on, we slowly crawled out of the Dark Ages of Dokémon and into the golden age of Jokémon. Jokémon brought Dokémon back to its comedic roots, but clung more to the Pokémon franchise than to the family members and their representative creatures such as the Russell Squirmy.

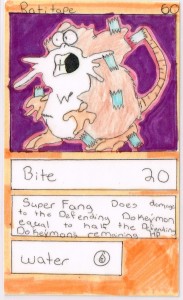

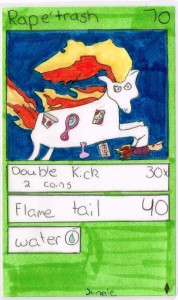

Jokémon were largely based off puns of Pokémon names. For example, Rapétrash (Rap as in rapid, not rape) was a play on Rapidash. Rapétrash is also a fire horse, like Rapidash, but with half eaten pizza and candy wrappers stuck to his coat. While perhaps not the knee slapper you would hope, it gave us a laugh at the time. Similarly, Ratitape is a play on the name Raticate. Ratitape, too, is hamster/rat-like, but he has tape stuck all over him. Surely, puns were not comedic gold in comparison to SNL and The Hangover, but the Jokémon represented a positive shift in the Dokémon evolution.

Jokémon were largely based off puns of Pokémon names. For example, Rapétrash (Rap as in rapid, not rape) was a play on Rapidash. Rapétrash is also a fire horse, like Rapidash, but with half eaten pizza and candy wrappers stuck to his coat. While perhaps not the knee slapper you would hope, it gave us a laugh at the time. Similarly, Ratitape is a play on the name Raticate. Ratitape, too, is hamster/rat-like, but he has tape stuck all over him. Surely, puns were not comedic gold in comparison to SNL and The Hangover, but the Jokémon represented a positive shift in the Dokémon evolution.

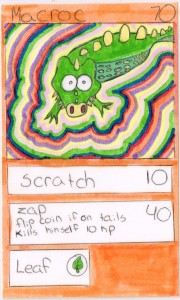

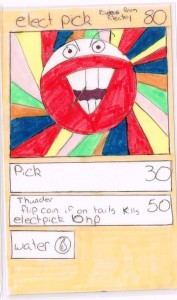

After the Jokémon period, David and I, continued with a mix between Pokémon pun characters and more unique original Dokémon creatures. During this period we experimented with different, colorful backgrounds, and more complex functions of attack abilities, such as Macroc’s Zap that required the flip of a coin. Many abilities now had the risk of self harm, but the HP values went up consistently, which offset the effect of the self destructive abilities. As you can see, even these two basic Dokémon have higher HP values than the final evolved forms of the earlier Dokémon, such as Hallowshell.

Electpick represent the continuing line of Jokémon, being a “funny” version of Voltorb, while Macroc was likely pulled form a real world alligator/eel, if not a dream I had.

Electpick represent the continuing line of Jokémon, being a “funny” version of Voltorb, while Macroc was likely pulled form a real world alligator/eel, if not a dream I had.

It’s clear that David and I figured out that odd and obscure numbers in HP and attack power did not work, by this time. We rarely actually played the game, but when we did, we did not like feeling we were in a math lesson. We wanted it to be fun, though we spent the majority of the time feverishly churning out card after card. The cards lost their novelty with our parents early on, so the rare occasion that we had to show a new friend our work became the only reward we received. And yet we continued making hundreds of the cards.

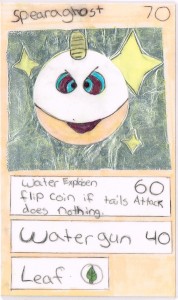

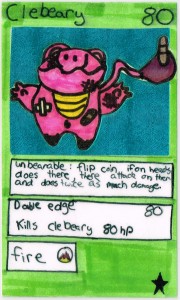

One day we got our hands on a collection of patterned foil. I forget if they had been a gift, or part of some delectable treats wrapping, but seeing as we loved holographic Pokémon cards, we did not miss our opportunity to create holographic, or foiled, Dokémon cards. Cutting and gluing squares of the patterned, colored foil to an index card, we then clipped out the Dokémon we had drawn on a separate piece of paper and glued it on top of the foil before laminating the whole thing. It added a lot of time to each card we made in such a fashion, but the result seemed worth it. Clebeary and Spearaghost are two examples of Holographic Dok émon cards.

émon cards.  It seems that Spearaghost‘s foil might even be run-of-the-mill aluminum foil, perhaps the first or last of its kind. The first if the idea of foil struck us before the colored foil came into our possession; and the last it represents the exhaustion of our colored foil resource. The characters, as you can see, are clipped from printer paper and pasted on the foil, which in turn it pasted to the complete index card. Clebeary’s tail even hangs over the edge of the foil, illustrating perfectly the multiple levels of these cards.

It seems that Spearaghost‘s foil might even be run-of-the-mill aluminum foil, perhaps the first or last of its kind. The first if the idea of foil struck us before the colored foil came into our possession; and the last it represents the exhaustion of our colored foil resource. The characters, as you can see, are clipped from printer paper and pasted on the foil, which in turn it pasted to the complete index card. Clebeary’s tail even hangs over the edge of the foil, illustrating perfectly the multiple levels of these cards.

Also clear from these two foiled cards, is the continued growth in complexity of the Dokémon. Spearaghost again illustrates the use of a coin in its first ability, and Clebeary furthers the decent into darkness with the suicidal ability Double edge, which may damage an opponent a whopping 80 HP, but also does the same to itself. Furthermore, Cleabeary is clearly injured, as is made clear with the scuff marks and the Band-Aids. This demonstrates the ultimate path Dokémon took, which is far different than the kid friendly Pokémon franchise. In Pokémon nothing ever died, nor did anything ever get as injured as Clebeary even. Perhaps these minor injuries hint at the ultimate downfall of Dokémon, for the cards became far darker and more violent in the end.

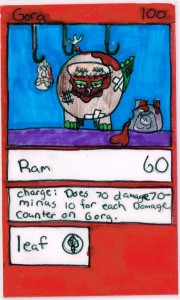

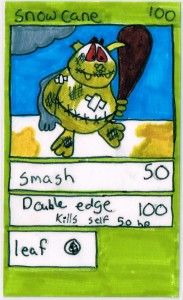

With additions such as the murderous Gorg, and the vulgar Snowcane, i wouldn’t be surprised if we didn’t capture our parents attention once more, only not in a good way. It’s clear the wounds were deeper, requiring stitches even, and the kind nature of the early Dokémon had been replaced with a malevolent one. By this time the HP counts had risen to the maximum 100, even for the basic Dokémon, so we no longer had room to grow, only stagnate, and create morbid shadows of the once fun, humorous card game cards. I imagine hormones were beginning to brew deep within us, angst too, and puberty crouched on the horizon.

With additions such as the murderous Gorg, and the vulgar Snowcane, i wouldn’t be surprised if we didn’t capture our parents attention once more, only not in a good way. It’s clear the wounds were deeper, requiring stitches even, and the kind nature of the early Dokémon had been replaced with a malevolent one. By this time the HP counts had risen to the maximum 100, even for the basic Dokémon, so we no longer had room to grow, only stagnate, and create morbid shadows of the once fun, humorous card game cards. I imagine hormones were beginning to brew deep within us, angst too, and puberty crouched on the horizon.

In the end, we put Dokémon away, as we all must do with childish things. The cards remained in a toolbox, in the crawlspace beneath a house, until just recently, when I retrieved them in order to share them with the world.

If you’d like to see a more complete gallery of Dokémon cards please visit my brother’s website at Hugyu.